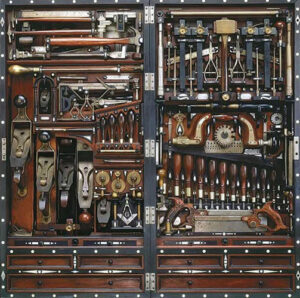

The aesthetic delight perennially experienced through the careful work of craft-filled hands is – to paint, to carve, to build, to garden or to invent new culinary offerings – perpetually conserved and cannot be destroyed by contemporary technological advancements. That delight will be invariant despite the advent of digital processes or feats of artificial intelligence. In our previous post (September 11, 2024), we cited an excerpt from a 1901 Frank Lloyd Wright speech.[1] In another passage of that speech, Wright used the text of Victor Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris to introduce two concepts:

- “The Machine was the great forerunner of democracy” … i.e., as books democratized access to knowledge.

- “Ceci tuera cela.” (“This will kill that.”): the famous slogan of Claude Frollo, the archdeacon of Notre-Dame in Victor Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris (popularly known as “The Hunchback of Notre-Dame”), as he touches a printed book and glances nostalgically at the cathedral towers …

Jennifer Gray, guest editor of the Summer 2020 Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly,[2] and the September 12, 2023, blog post of the St. Tammany Parish Library Blog of Covington, Louisiana,[3] taken together circumscribe the significance of Wright’s comments and the context of Victor Hugo’s work in the syncopation between the phenomena of progress and preservation.

From Jennifer Gray’s introduction:

“In 1901 Frank Lloyd Wright delivered a seminal address called “The Art and Craft of the Machine” to an audience at Hull House, an organization that offered social services, such as education, childcare, and legal aid, to poor communities in Chicago. The themes Wright outlined in his talk would preoccupy him throughout his life, namely the relationship between machines, education, architecture, and democracy. Calling the machine “the great forerunner of democracy,” Wright invokes an argument advanced by the French author Victor Hugo in Notre-Dame de Paris in 1831 that reflects on the power of the printed word. Before the age of Gutenberg, architecture centered on the handicrafts and was the “universal writing of humanity.” The invention of the printing press—arguably the first great machine, Wright points out— transformed architecture but also social relations. Books democratized access to knowledge. While any individual book may appear ephemeral or fragile, the sheer number of them, the number of people reading them, and the ability to reprint them renders “printed thought … imperishable … indestructible.” Widespread literacy and access to knowledge ultimately contributed to the democratic revolutions of the eighteenth century, including the American Revolution.

Wright embraces the machine, broadly speaking, as capable of reducing human labor and expanding lives and “thereby the basis of the Democracy upon which we insist.” …, the machine reduces waste and lowers costs so that “the poor as well as the rich may enjoy to-day the beautiful surface treatments of clean, strong forms.” Indeed, throughout his career Wright would experiment with various ways to harness the advantages of machine production to design quality, affordable housing for large numbers of people. …”

From the St. Tammany Parish Library Blog:

“Efforts to update the Notre Dame cathedral, which included replacing its stained-glass windows with clear glass, disgusted writer Victor Hugo. Hugo was fascinated by the cathedral, visiting it many times in the late 1820s. He struck up a friendship with a priest who explained to him the symbolism inherent in many of the building’s architectural details and statues. Enamored, Hugo hoped to preserve the cathedral from any further meddling through his next novel project.

…, Hugo did not just use the past as window dressing: he was interested in recreating a long-departed time and place down to the smallest detail. The story is set in fifteenth-century Paris, complete with its widespread superstitions, rigid social hierarchy, and of course, its gothic architecture.

While one might expect a book born of the desire to preserve historical architecture to be at best a dry read, the continued popularity of the story proves otherwise. Hugo’s novel remains a deeply affecting tragedy, powerful in its depiction of humanity’s tendency towards both cruelty and compassion. …”

The Tammany Parish Library Blog Post highlights Victor Hugo’s ulterior, preservationist motives that contain the seed of a thought Frank Loyd Wright will later sample and ironically reuse to advocate for the displacement of stalwart, edificial cultural landmarks with the nascent promise of imminent technical advancement. Interestingly, Wright is likewise arguing for the preservation of something precious at the deeper level of experience, the art in craft. This dance of ideas that are simultaneously opposing and reinforcing emulates the choreography of the cycle of life/death and reflects the gleeful contradictions of everyday living. The ‘old’ gives way to the ‘new’ in the fullness of cyclic time while somehow and magically preserving the essence of past delight with enough veracity so that it lives on, anew but different, and thankfully invariant at the core.

We cannot discuss tool selection and our associated craft aspirations without an inevitable confrontation with the question of why we find a particular result pleasing or even beautiful. Academics of the last century debated the efficacy of the word “beautiful” due to the often oligarchical or elitist subjectivity of past efforts to define beauty.[4] We believe that angst was settled in the thoughtful embrace of ‘the beautiful’ by Dewey and Joyce.[5],[6] Also in that century, when Christopher Alexander[7] writes about the universal “quality without a name,” he is referring to conservation of the delight felt while experiencing the presence of that earnest aesthetic spirit – the phenomenon connecting Wright’s intent with Hugo’s work. Hugo’s work passed the presence of that spirit forward through time to Wright as if in an ephemeral relay to celebrate the immutable and universal sense of aesthetic delight. That ‘timeless way’ of work guides the collective effort to increase delight in our environment and our artifacts. When gently inspired, consciously or unconsciously, by the aesthetic whispers from past artfulness, we find the wit to imbue our wielding of the tools of our time to experience delight as well.

Frollo’s prophecy is false. The book did not kill the edifice. Contemporary buildings still aspire, in their way, to achieve the artful presence of Notre Dame. And, current digital tools, 3D Scanning|Printing, ChatGPT, et. al., will not make moot the careful work of our hands for the sake of craft and art.

_______________________________________________

[1] Daughters of the revolution, Illinois, excerpt from “The new industrialism,” Part III, pages 87-119, Digital Public Library of America, https://dp.la/item/93eb1c929b351123f792553233d561cc (Catalog Record: The new industrialism. Part I. Industrial… | HathiTrust Digital Library).

[2] Introduction by Jennifer Gray, guest editor of the Summer 2020 Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly, The Basis of Democracy: Frank Lloyd Wright on Community, Education, and Opportunity.

[3] Spotlight: “The Hunchback of Notre-Dame” by Victor Hugo, September 12, 2023, © 2024 St. Tammany Parish Library Blog

[4] Foster, H. (1999). The Anti-Aesthetic. New York, New York: New Press.

[5] Dewey, J. (1934). Art as Experience. Originally delivered as the first William James Lecture at Harvard (1932). New York, New York: Perigee Books by G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

[6] Mason E. & Ellmann R., Editors (1964). The Critical Writings of James Joyce. “Chapter 33: Aesthetics, 1903/04,” Pages 141-148. New York, New York: The Viking Press.

[7] Alexander, C. (1979). The Timeless Way of Building. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.